Alternative biographies

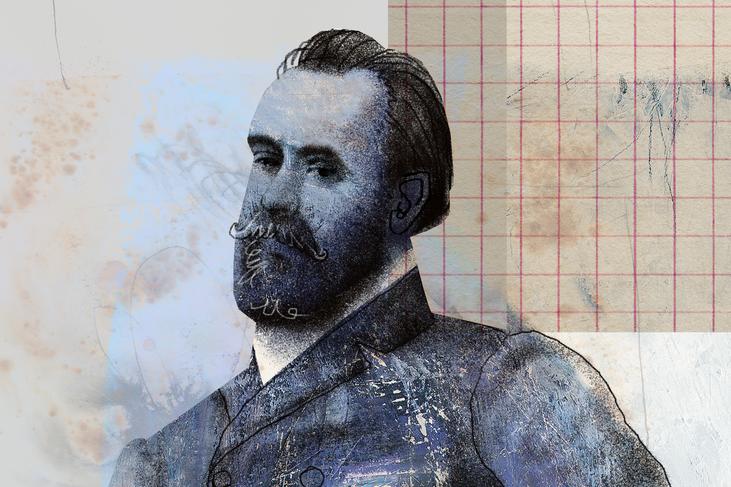

Baltazar Bogišić

Photo gallery

He lived in different world capitals, but mostly in Paris, where he was a member of the French Academy, the first man from this region after Ruđer Bošković. And like Ruđer Bošković, he was a man of the world. He was born in a prominent family in Cavtat, which had a wide array of commercial and maritime businesses, and from early age he showed remarkable curiosity and affinity for sciences and learning. As a 13-year-old he already graduated from primary school and a private nautical school in Cavtat, followed by a private school that taught subjects of the then lower secondary school. His father objected to his son’s further education, thinking that his Baldo was destined to be the family heir and was worried he might leave Cavtat if he were to pursue higher education. However, after his father’s sudden death, Baltazar decided to continue his education in Venice and subsequently at the Faculty of Law in Vienna (1859). During his education in Vienna, he attended courses in law, philosophy, history and linguistics at universities in Berlin, Paris, Munich, Giessen and Heidelberg. In 1862 in Giessen, he was promoted to a doctor of philosophy, and next year he was appointed as a librarian in the Slavic department of the Imperial Court Library in Vienna. There, he expanded his knowledge about Slavic history, languages and culture and he became interested in legal customs of South Slavs, and was then promoted to a doctor of legal sciences in 1865. As librarian in the Court Library he met many Slavic scholars and writers and became an adherent of Slavophile ideas. At the end of 1869, following a two-year service in the Ministry of Defence in Vienna, he accepted the invitation of the university in Odessa, which selected him to be a tenured professor of comparative legal history of Slavic nations. At the suggestion of the Montenegrin Prince Nikola Petrović-Njegoš (ruled from 1860 – 1918), the Russian Emperor Alexander II entrusted Baltazar with writing the Civil Code of Montenegro, and at the same time awarded him the title of the legal advisor to the Russian government. And he actually spent the next 15 years studying, preparing and writing this law, for which reason, and thanks to the awarded stipend, he became fully independent in his work and moved to Paris. After many years of preparation, and three readings, the Civil Code was adopted by proclamation and it came into force in July 1888, and subsequently Bogišić deservedly retired. He spent his time finishing the long-abandoned works, conducting new scientific research, collecting archival materials and travelling for professional reasons. However, in the wake of persistent pleas by Prince Nikola he accepted the position of the Minister of Justice of Montenegro in order to be able to supervise the practical implementation of the Civil Code. This resulted in some amendments and improvements to the original version and a second edition, that was published in 1898, after which he retired fully and again devoted himself exclusively to scientific work. He died suddenly in Rijeka, on his way from Paris through Vienna to his native Cavtat, and he was buried in his family tomb in Cavtat. He was succeeded by his only sister Marija Bogišić-Pohl (1837 – 1920) who devoted the rest of her life to preserving the memory of her famous brother. Together with a library which contains approximately 15,000 books and a print collection of over 8,000 pieces, his correspondence comprises over 10,000 letters that he exchanged with more than 1,000 persons, societies and institutions that he worked or was friends with. In 1914, at the Cavtat promenade, a monument created by sculptor Petar Pallavicini (1886 – 1958) was erected in his honour, and from 1958 onwards, his museum is housed in the Renaissance-style Rector’s Palace in Cavtat.

Bogišić’s overall scientific activity was indeed extensive and diverse but, internationally, his most famous work is the aforementioned Civil Code. Namely, Baltazar thought that modern writing of laws should be based on the traditional, popular legal understanding and he did not accept the blind adherence to the principles of Roman law. He therefore applied this methodological principle to the Montenegrin Civil Code and he translated the living law into legal provisions, wanting it to reflect contemporary needs and national distinctiveness. He thus codified patriarchal provisions of the Montenegrin kinship-tribal order into law, and since this type of codification of customary law was new, his Civil Code drew the widespread attention of scientists and jurists. It was translated into French, German, Russian, Spanish and Italian, and even Japanese experts consulted it. Bogišić himself published an article in which he explained the way he collected and codified customary law in the Civil Code. We should mention that, among other things, Baltazar Bogišić travelled extensively collecting legal customs, and was the first in our region to envisage a questionnaire of 352 questions (the so-called Naputak za opisivanje pravnijeh običaja koji živu u narodu, 1867) that he sent to all South Slavic countries in order to collect the necessary data. So, for example, he translated the Latin legal proverb with the popular proverb: “What is born crooked even time cannot straighten.”