Alternative biographies

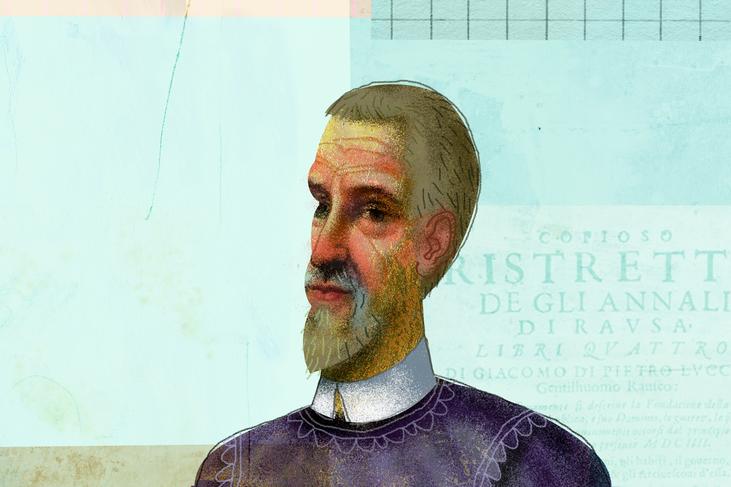

Jakov Lukarević

Photo gallery

Findings about this centuries-old rift provided us with a key to understand certain individuals and their activities, including the life and work of the Dubrovnik patrician and historiographer Jakov Lukarević (Luccari) and his contemporaries, like the Benedictine historiographer Mavro Orbini, that could be understood in this context. Jakov Lukarević was born in 1547, as the son of Duke Petar Lukarević and Mare Bonda. In accordance with the social role of the patrician class, Lukarević became a member of the Major Council in 1571, and as a prominent patrician performed an entire series of duties in the service of the Dubrovnik Republic. He was a member of the Minor Council, judge in the Criminal Court, and twice the tribute ambassador. He sailed almost the entire Mediterranean, and travelled overland through Pannonia, Bulgaria all the way to Turkey. In 1605, his great historiographic work entitled Copioso ristretto de gli annali di Rausa was published. The work is composed of four books, and contains excerpts from Dubrovnik chronicles about the Republic from its establishment until 1604. The work itself was dedicated to Marin Bobaljević (Bobali), a Dubrovnik patrician. In the introduction Lukarević tells him that he considers historical writing to be “the most difficult task a man can impose upon oneself…” Jakov here makes a clear distinction between historical events and personal interpretations, the latter always being influenced by prejudice and passions, which is the heaviest burden of historical writing. This conscious remark about the relativity of interpretations of historical events perhaps best describes the political climate in light of the rift in the Dubrovnik patriciate, that was reaching its culmination point, during the so-called Great conspiracy (1609 – 1612), at the exact time he was writing his work. The centuries-old conflict between the two clans, led by the Gundulić family on one side and the Bobaljević family on the other, sharply divided the other patrician families, so based on this division the Lukarević family became part of the Bobaljević clan. Lukarević’s work completely confirms this membership, not only by its dedication to Marin Bobaljević, but with its content as well, especially his interpretations of key events in Dubrovnik’s history. However, even with these “shortcomings,” Lukarević’s work is in accordance with similar historiographies of the time. Like Jakov, the Benedictine historian Mavro Orbini, author of the Kingdom of Slavs (1601), dedicated his work to the same Marin Bobaljević. In it, Bobaljević appears as a powerful patron, who financed the publishing of many books and had always been willing to give his wealth for his homeland. And although these two important authors praise his name, merits and virtues, what they do not mention is the fact that Marin Bobaljević was also a murderer, who fled Dubrovnik after he murdered Frano Gondola in 1589, one of the greatest lawyers and diplomats in Dubrovnik. Unlike the Bobaljević clan, which openly stood with the then European anti-Ottoman movement, the Gundulić clan tried to preserve a diplomatic balance between the Venetians and the Ottomans. Thus, the old patriciate rift was also reflected in the new era.