Alternative biographies

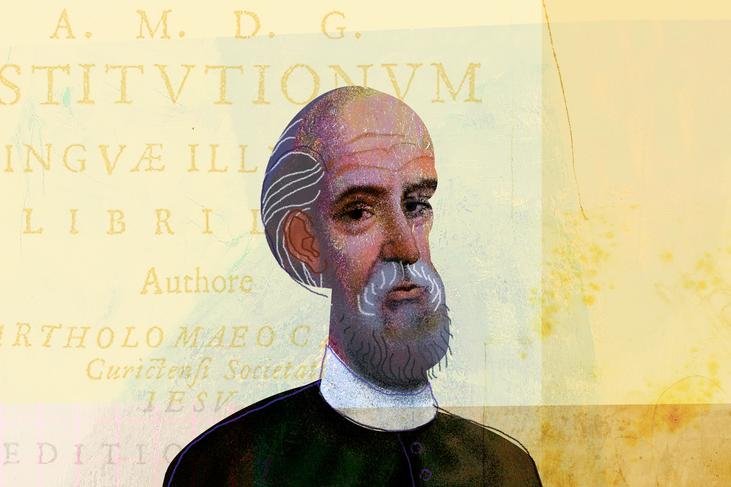

Bartol Kašić

Photo gallery

Still, the impetus to use language as a cohesive element of reformed Catholicism sometimes came from the peripheral regions themselves. And it was precisely in Dubrovnik where “an idea was born to translate the Holy Scripture into the spoken vernacular language.” When asked which among the Slavic languages would be most suitable for this purpose, the Jesuits responded to Pope Clement VIII that it was Croatian – lingua croatica, stating that the language was spoken by both the common and educated people in areas under Ottoman rule, that it is the root of all other Slavic languages, its pronunciation was “the most beautiful and sweet”, and it had the richest cultural history. This was the context that Jesuit Bartol Kašić lived and worked in. He was born on the island of Pag in 1575. He finished his primary education in Pag and Zadar. He continued his education in Italy, in the Croatian Collegiate in Loreto, and then in Rome. After joining the Society of Jesus, he studied in the Collegiate in Rome and in 1606 became ordained as a priest. In 1604, he compiled the grammar textbook for the needs of the Illyric Academy (1599) entitled The Structure of the Illyirian Language (Institutiones linguae Illyricae). In terms of the classical title, the name of the language – Illyrian language, was related to nations in the wider South Slavic territory. The Structure was supposed to be used as a language textbook for young monks – missionaries. This was also the first grammar of the Croatian literary language. Kašić spent time in Dubrovnik on two occasions; first, in the period from 1609 do 1613, when he wrote a work about prayer and meditation, intended for nuns in Dubrovnik nunneries. He departed Dubrovnik disguised as a merchant and travelled through Bosnia all the way to Belgrade. On his way back to Rome he met Croatians who escaped to Italy after Ottoman incursions. Bartol’s testimony about this encounter is the first written trace of Croatians in southern Italy. After his return from the second missionary journey, he again spent time in Dubrovnik (1620 – 1633). At the request of the Archbishop of Dubrovnik, in 1625 the Congregation for the Propagation of Faith instructed Kašić to translate the Bible. Kašić translated the New Testament into the Croatian language, specifically in the tradition of the Shtokavian dialect of Dubrovnik. The translation work was completed in 1629, and in 1631 the work was sent to the Congregation in Rome for inspection. However, they did not approve the printing of the work, and the translation itself was forbidden. In 1636, Kašić translated the Roman Ritual, important for the development of the standard Shtokavian literary language. Kašić left behind an unfinished biography with descriptions of his missionary journeys. He died in Rome in 1650. Why Rome decided not to print Bartol Kašić’s translation of the New Testament remained a secret for a long time. However, after a letter of the Bishop of Zagreb, dated 1633, was found in the archives of the Holy See, the reasons became clear. In his letter, the Bishop of Zagreb wrote to the Pope that he heard the Dubrovnik Archbishop wanted to print the translation of the Bible in the dialect of Dubrovnik and he asked that other bishops and heads of monastic orders in Dalmatia, Bosnia, Croatia and Bosna Srebrena give an opinion about the matter. The Pope established a commission that was supposed to study the matter and make a final decision on publishing Kašić’s translation. On 13 June 1634, the Holy See decided that the new translation of the Bible was superfluous and unnecessary. Kašić’s translation of the Bible was not printed until 1999/2000.